At first glance, implementing tariffs may seem like a straightforward and beneficial policy. After all, why not impose a tax on foreign goods and generate additional revenue for the government? However, the reality of how tariffs work is far more complex.

How Tariffs Work

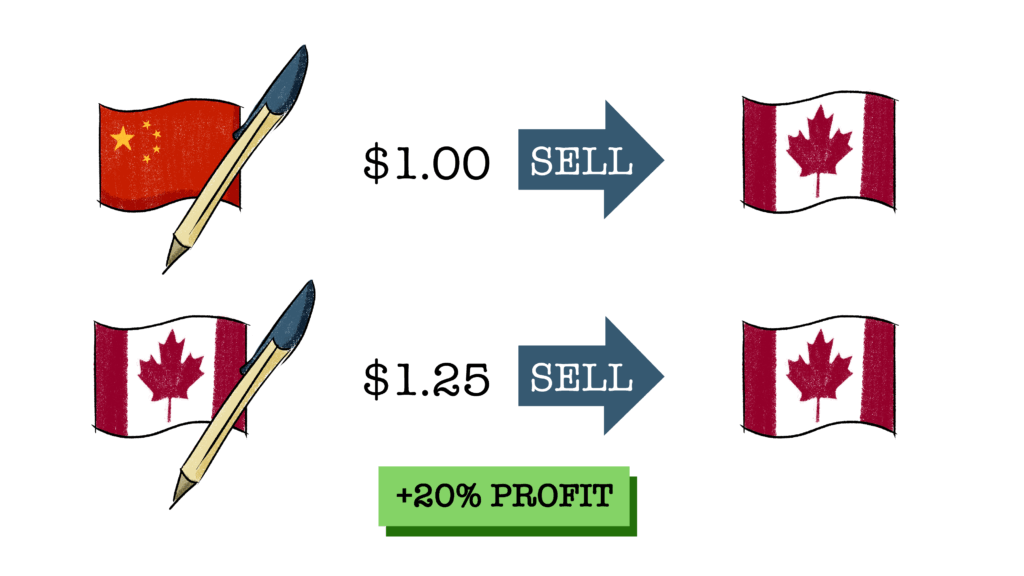

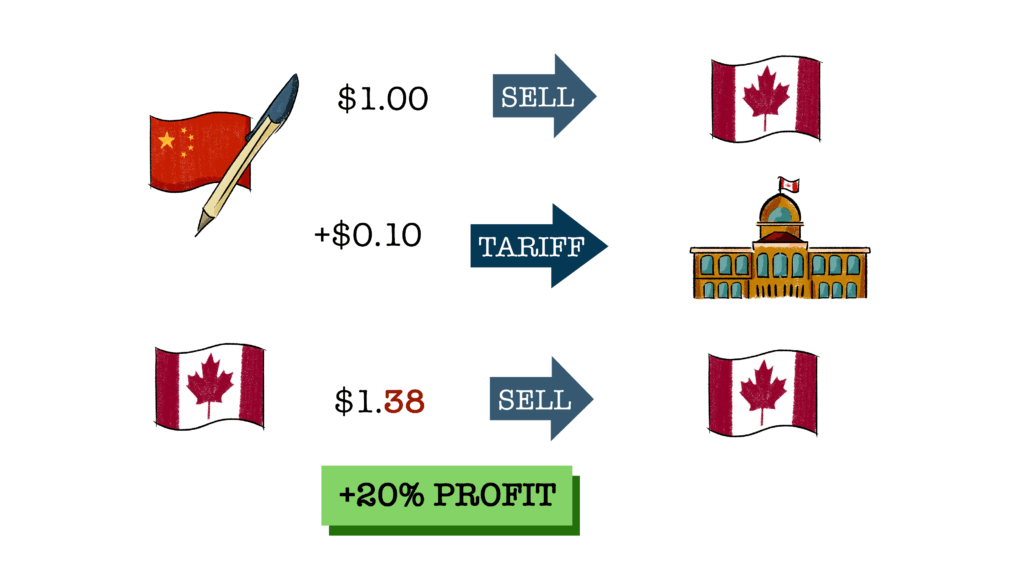

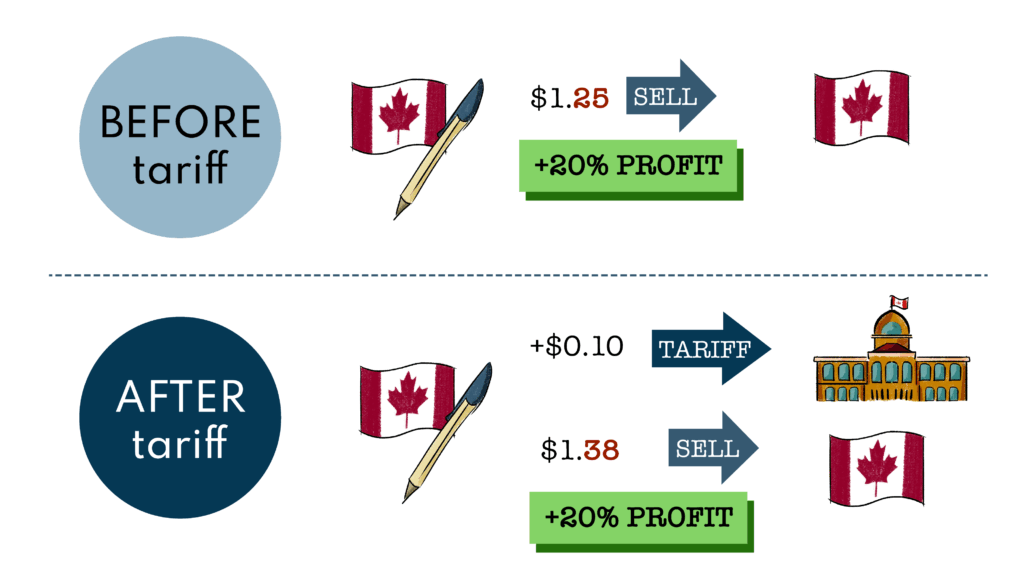

Let’s first look at how tariffs work. A tariff is a tax levied on imported goods and services. For example, consider a pen manufactured in China and sold to a Canadian company for $1. The company then sells the pen to Canadian consumers for $1.25, earning a 20% gross profit margin.

Now, imagine a 10% tariff is introduced. The Canadian company must now pay $1.10 for the pen — $1 to the Chinese manufacturer and $0.10 to the Canadian government.

Importantly, it is the importer, not the foreign manufacturer, who pays the tariff.

To maintain its 20% gross profit margin, the company raises the final price to $1.38. This increase reflects the added cost of the tariff, which is passed on to consumers — assuming the company has the pricing power to do so. If not, its profit margin would shrink.

Interestingly, the gross profit per pen increases from $0.25 to $0.28. This is because the company adjusts its pricing to preserve margins, anticipating lower sales volume due to the price hike.

Historical Use of Tariffs in North America

Tariffs have played a significant role in the economic history of North America. According to Professor Douglas Irwin of Dartmouth College, the United States has used tariffs for three primary purposes across different periods: revenue generation, trade restriction, and reciprocity.

In the late 18th century, the newly independent U.S. relied heavily on tariffs as a source of federal revenue. Between 1790 and 1860, tariffs accounted for approximately 90% of federal income. Similarly, British colonies in what is now Canada relied on tariffs as their primary source of public funding before Confederation.

From the 1860s to the 1930s, domestic taxes — such as those on alcohol and gasoline — gained prominence. During this period, the U.S. primarily used tariffs to protect domestic industries, with tariffs still accounting for around 50% of federal revenue.

In Canada, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald introduced the National Policy in 1879, which combined infrastructure investment, population growth initiatives, and protective tariffs aimed at shielding Canadian industries from American competition.

However, the use of tariffs has not always been beneficial. In 1930, President Herbert Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, significantly raising tariffs on hundreds of imported goods. This move triggered international retaliation and deepened the global economic crisis following the Great Depression.

The Shift Toward Trade Liberalization

Following World War II, the global approach to trade underwent significant changes. The creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) — the precursor to the World Trade Organization (WTO) — marked a move toward reducing trade barriers and promoting international cooperation. Canada followed suit, gradually lowering tariffs while maintaining targeted protections, particularly in the agricultural sector.

How Tariffs Work Today: Still Relevant

Despite the trend toward liberalization, tariffs continue to be a powerful tool for governments. Recent examples include the U.S.–China trade war and the imposition of targeted tariffs on steel and aluminum. These measures demonstrate that tariffs continue to serve both economic protection and geopolitical strategy.